ALBANY GEORGIA in 1963

Foreword About Albany, Georgia in 1963

“Albany Georgia, GA in 1963” is an article written by Peter de Lissovoy. Excerpts below were copied as written. This writer had the pleasure of interviewing Peter in 2022 and was inspired by his perception and analysis of America’s civil rights struggles in 1963 and 2022. “Spot-on” is my analysis.

As we look at America today and grasp how far some have traveled mentally and how too many are in the same place, it is a sad commentary on humanity. The Civil War is still raging in the hearts and minds of large segments of the nation. Racism is rampant and “love one another” is scarce. Honesty, integrity and truth are “just words without meaning” in the minds of millions of Americans. Power is the word, and control is the method! Where are the Peter de Lissovoys of 2022?

Albany GA in 1963

by Peter de Lissovoy

“In Albany in 1963, when I arrived in town, events had a little passed Southwest GA by, or so some people felt.

When Dr. Martin Luther King had been in town in 1962, people had felt themselves to be essential actors. They also felt that they had made Dr. King. Probably a lot of little towns felt this way and still do.

The (Albany, Ga in 1963), fathers were pretty slick… and Chief Pritchett was no Bull Connor, and some say Dr. King moved on to riper vineyards. By 1963, after jail time and sacrifice, nothing had changed. I heard bitter, dispirited talk, all protests had waned, and in SNCC there was concern for how to reinvigorate the Movement in Albany, which was expressed to us newcomers as a charge to get to know the kids and stir things up.“

C.B. King an Albany, Georgia in 1963 Leader

There was a stalwart of African American professional people who had started the Movement years and years ago in Albany and kept it going over long hard years and times through their vision and sacrifice and by sheer guts and nerve — from the forties and well before that even. These were people such as Dr. William Anderson, C.B. King and Slater King, and of course their father before them, and Reverend Wells, Thomas Chatmon, Bo Jackson and his wife, and many, many others, deacons, teachers, doctors, whom we would eventually come to know a little . . .”

“C.B.’s brother Slater King became the head of the Albany Movement at this time. Slater was a well-off real estate man. Like C.B. he had a ready smile and a booming warm deep voice, but if C.B.’s smile, whether for us kids or for the cats on the corner, through whose midst he had to traverse to his Harlem office, always had a wry twist in it as if he couldn’t help seeing hard truths and sharp ironies. Slater’s smile was just plain big and warm and welcoming . . . Between these two men a whole contingent of SNCC workers felt at home and protected and welcomed and that they really had some powerhouses between themselves and death at the hands of a lynch mob.”

SNCC Volunteers Played a Part

“Just the same, the Movement spirit had to be maintained, the fires fanned, and everybody do their part in national events and the broad challenge. This was the charge given to the SNCC volunteers. . . The truth was that the efficacy of Dr. King wherever he was, depended on the backdrop of rumblings in Albany and everywhere else.“

Editors interject a couple of sentences. Dr. King was the Voice of Black America. His presence and leadership generated courage, hope and a desire to die for the Movement. In fact, many did die. This respect was cemented in the minds of his followers mentally. . . his physical presence was not its source.

Back to Peter. . .

Leaders Keeping the Flame Lighted

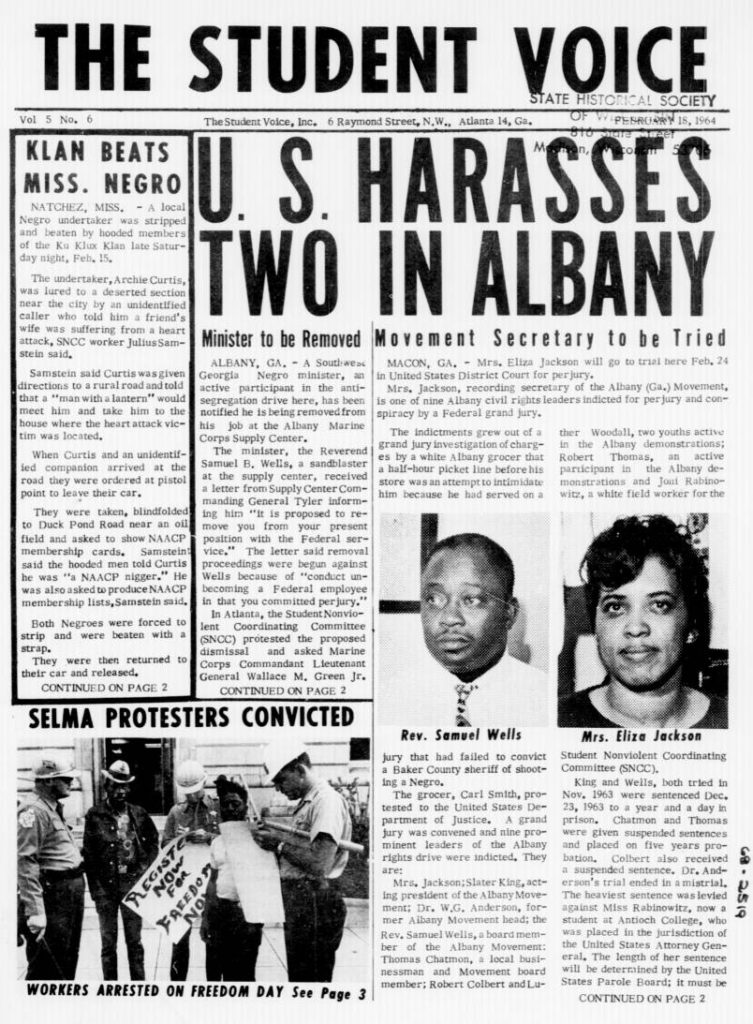

“In these circumstances, with people no longer fervent, the task of keeping the flame alive fell to those rock-solid preachers who would still lead the mass meetings now when other preachers had grown weary and no longer would — firebrand Reverend Samuel Wells was such a tireless one — and to the SNCC kids, led by Charles Sherrod.

Both of these men, one young, the other middle aged, filled me with awe and silence. Reverend Wells was short and powerful and somehow vivacious and solemn at once and black as coal and unsmiling. He preached fiery sermons at the mass meetings and never let up on people, always reminding them of what time it was — time for ever more sacrifice and “to keep their eyes on the prize.

The essential dignity and gravity of the man left me quavering.“

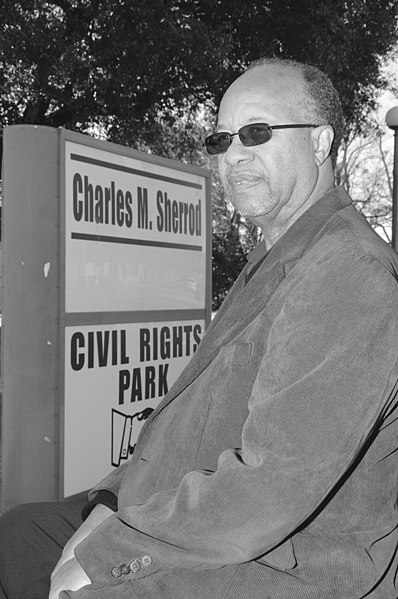

Charles Sherrod A SNCC Apostle

“Charles Sherrod was the head of SNCC in Albany, one of the original SNCC apostles who had gone to various locations in the South to stir things up. He had always been in favor of having whites be part of the protests, according to what Randy Battle has told me. According to Randy, the disagreement in SNCC about whether or not whites should be part of things, which I had thought marked SNCC’s later days, was part of the inner SNCC dialogs from the outset, and Charles Sherrod, whether from a larger vision or as a tactic, always believed in bringing in white kids and he did so in Southwest Georgia from about 1961.

You might say everybody had a bit of a problem with Sherrod, because that was partly what he was there for, to keep a pack of boisterous SNCC kids in line.“

Randy Battle Learns to Read

“Even Randy was always fighting with him, who loved him. It was a game between them every night to see if Randy could steal the keys to one of the SNCC cars somehow or other.

Sherrod taught Randy to read, who became a voracious reader, and read all the white kids’ Kerouac novels and C. Wright Mills books in 1963.

At John and Pat Perdew’s wedding reception in 2004 at the Art Center, I said to Sherrod: “Everybody remembers how you didn’t let them have any fun at all, Sherrod.”

“I was trying to keep you alive!” he laughed.“

SNCC United Blacks and Whites in Hope

“SNCC brought in a contingent of college kids from up North in the summer of 1963. Now all the kids would get an indoctrination and be sent out to the little towns, John Perdew and others to Americus, Wendy Mann to Dawson, Phil and I assigned to CME (after the CME church, but it also meant Crime, Murder, and the Electric chair). And so, we all attended a big meeting for the sake of enlightening us.

Some of the old volunteers were leaving and going back to college or perhaps being transferred by SNCC elsewhere. I remember that changing of the guard, sitting at the feet so to speak of the veterans, white and black, whose time was up. We had a big meeting, and the idea was to pass some wisdom along to the newcomers.”

PRATHIA HALL – THE FACE OF AMERICA’S REALITY

“Prathia Hall, who had the unenviable task of inducting us into black culture so we could “move with the people” (Prathia’s phrase, who was a middle-class Negro herself I suppose, but so brave and beautiful, yet there was to my eye anyway a comical aspect of us white kids from up North trying to learn about black mores before heading off to jail)

You could see in their faces and bearing that they had been through something. There was that in their eyes of knowing the score that was just like the locals’, having seen suffering and having suffered, something gentle and knowing, beyond perplexity now. I wondered if I would measure up to these people, and of course I never did. You could see how the people in the town loved these kids, and in turn their love for the community.“

Editor’s Note: The harsh realities of racism in America, stamped in the hearts and souls of a person, have visible signs in appearances and actions. Unlike Peter, many white people cannot fathom what it does to a person’s identity, self-esteem and courage. It’s a fight many blacks live with every day. . . in 2022.

“Black and I’m Proud”

“I remember that first SNCC indoctrination meeting, where handsome gang leader Eddie Brown displayed his credentials by impulsively pulling up his T-shirt to shamelessly show off his bullet wounds, grinning like a charming scoundrel, showing his gold tooth. We middle-class white kids from up North obliged by admiring the bullet entry scars. The Movement in Albany, in unheralded times, in the doldrums, needed these gang guys who could reach all kinds of kids, who had the guts to march in obscurity now that Dr. MLK had split town, kids who maybe didn’t even recognize it as obscurity, for whom society and the sanctioned life were always totally obscure, who understood their own wild deeds and joy and glory as the only possible light in obscurity.“

The Civil Rights Movement Reached Thousands

“. . .the Civil Rights Movement was the work of thousands and thousands of real human beings who did their bit and had their heroic day just as any regular Americans would have done in their situation. Daily life and the Movement were all mixed up and the heroic work was being done by ordinary people who just felt like doing it and saw the need for doing it.

By 1963, in Albany GA, the Civil Rights Movement work was mostly being done by the kids, sometimes very young ones.“

Peter de Lissovoy Recalls His Arrival in Albany

“In a July 1963 field report for SNCC headquarters in Atlanta, I wrote:

When I arrived in Albany, somebody or other told me to go to work in CME [after the CME church there — and Crime, Murder, and the Electric chair]. "This is a very tough area. There is a gang there. These are some bad cats. See what you guys can get together."

So, a couple days after we arrived there, Phil Davis, an iron worker, Socialist Worker, who combed his black hair back in a ducktail like Elvis, from California, and I were hanging around the baddest part of Albany, CME, trying to get gang leaders interested in integrating the swimming pool . . .”

The Pool at Tift Park

“In 1963, the town fathers of Albany, GA, had sold the municipal swimming pool to Albany Herald publisher James Gray to avoid integrating it. They had their finger to the wind, and it was a slick move by the segregationists because President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Law not much later.

So, the white kids would keep their now private pool, and the black kids would go on swimming in muddy Flint River. It was a hot summer, and it was easy for us SNCC agitators to agitate the kids about the pool. “ Gonna be a march tonight on Tift Park to protest the pool. You gonna be there?” And kids say sure — but it depended how things went down — who would be there — and who would lead.“

A “Pool” of Jim Crow

“The pool was an obvious reminder of the unfairness that was the social norm, but so was everything — you couldn’t open your eyes or turn around without seeing Jim Crow everywhere, white and black schools, drinking fountains and the rest, with a police state to back it up. So, the irony was that the “to do” list of SNCC and the Movement was endless, and it was the town fathers’ selling their town pool to publisher Gray that made Tift Park swimming pool a potent symbol for us.“

The March

“ We met in a school playground. Round and round the block we marched, gathering momentum, to call the kids down, off the stoop, off their bikes, from behind the houses and in the alleys, past their mothers rocking on the porches holding funeral parlor fans, calling shrilly their objections — ‘No, no, y’all! Don’t y’be in that mess no more!‘

The March: A Symbol of Dignity

“The kids eluded mothers and fathers sometimes flailing at them with those paper fans, with no more efficacy than using a flyswatter on a laughing stream to make it stop.

There was awe and purpose, but also experiment, among the kids who struck out toward downtown and Tift Park with that forbidden swimming pool, next to it a statue overgrown in verdigris of Confederate Tift himself, founder of Albany, who sold salt pork to the Rebel army. Despite the bloody pictures, the black kids in Albany, GA, were never cowed or bowed down, but full of hilarity, gaiety, and irreverence.

We were naturally afraid. . . The misconception among outsiders was that the kids marched because they needed to get something, but it was just because of who they already were.“

Jailed Again in Albany, GA in 1963

“Shortly, we were in jail again, in Albany, after the march on Tift Park pool, originating from CME. There were no cameras on for that march, no media attention, few spectators at the end, the local folks in the streets and on their porches at once moving back for safety into the obscurity of their doorways, as we never made it past Oglethorpe Avenue, and the cops of course, hauling us away in a weird night and moon-drenched obscurity, quietly cursing as they threw us in the wagon.

On the way to jail, when the paddy wagon went around a corner, James Daniel made us all jump up against the inside wall of the wagon, causing it almost to turn over. When we did this, the cops braked, and one jumped out and beat on the side of the wagon with his club.

Shortly we would all be shipped here and there around the country to yet more obscure prison facilities to wait out weeks till bail could be raised.“

Songs of Praise and Comfort

“In the dim yellow light that left the corners of the cells in shadow, the night seeming to tower away from us as if it were the grief-soaked past of this land, we sang freedom songs into the early morning. I’ve never enjoyed singing so much. It kept the loneliness and horror of the steel cages we were in at bay. But it was more than to keep up our spirits. Our singing transformed the degradation of the cells to which we had been consigned by the Powerful.

The singing seemed inevitable, a culmination; you would have had to put tape over those kids’ mouths to stop them singing through the night. We felt jubilant and on a road to something. Southern jails were segregated along with everything else; cracker jailbirds were still — white. Some of them protested forlornly a sad protest of their own that they wanted some sleep. “Sheddap! You goddam freedom riders!” Freedom songs rang from one end to the other and integrated the joint and kept the jailbirds wakeful and almost raised the dead.

Paul and Silas bound in jail,

Had nobody to go their bail …

Hold on … hold on …

That tune was my favorite. I loved singing that one.“

Peter de Lissovoy: Living in Albany, GA in 1963